- SEA LIFE, Shark Valley

Discover our Shark Species

Here at SEA LIFE Sydney we have 14 different species of sharks including our giant Grey Nurse Sharks and our local Port Jackson Sharks.

Book Now

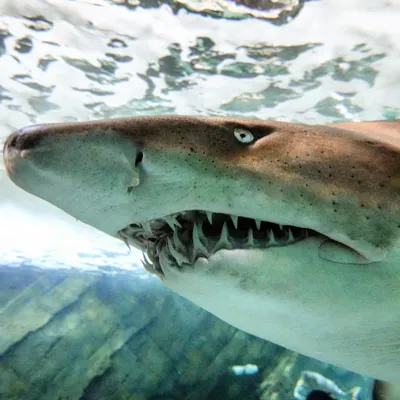

Grey Nurse Shark

Despite its fearsome appearance and rows of sharp teeth, the Grey Nurse shark offers no threat to humans and is, in fact, a superbly adapted fish-eater, usually swallowing its prey whole. During the 1960s and 1970s, the population of the Grey Nurse shark declined sharply and in 1984, they became the first shark species in the world to be awarded protected status. SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium supports conservation measures to protect the species, such as through the establishment of marine parks where fishing is prohibited.

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Vulnerable

However the east coast population is listed as critically endangered.

Blacktip Reef Shark

The Blacktip Reef shark is habitually identified by its prominent black tips on its fins. This species can grow up to 120 centimetres in length and feeds on crustaceans and other small fish. They are typically found lying within shallow, inshore waters over reef ledges and sandy flats of tropical and sub-tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific region. However, they sometimes appear within brackish and freshwater environments too.

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Vulnerable

Whitetip Reef Shark

The Whitetip Reef shark is widely found across the Indo-Pacific region nestling near caves as well as the coral heads and ledges of coral reefs. Whitetips are more slender in body shape than other sharks, have oval-shaped eyes, characteristic white tipped fins and can grow up to 1.6 metres in length. Its diet consists of eels, octopus and crustaceans.

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Vulnerable

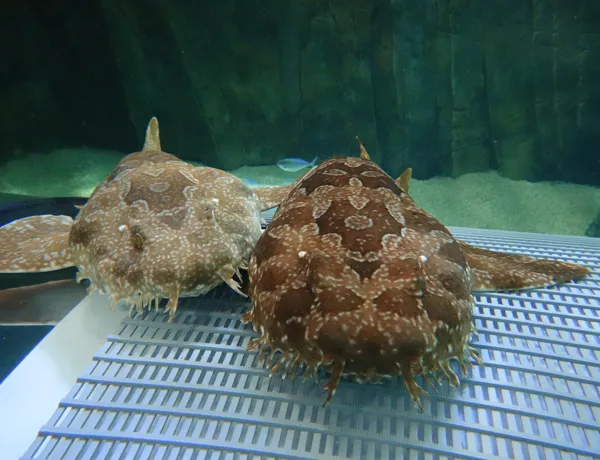

Wobbegong Shark

Wobbegong sharks are species of carpet sharks found in the temperate and tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific Region. The origins of the name ‘Wobbegong’ is derived from the Australian Aboriginal language meaning ‘shaggy beard’, a reference to the whisker-like growths around its mouth. Unlike other sharks, the Wobbegong’s skin is patterned, giving the appearance of light and dark blotches which assist its ability to camouflage on the ocean floor. Most species of Wobbegong grow up to 1.5 metres in length.

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Least concern

Epaulette Shark

The Epaulette shark is a small slender shark that has one large black spot on its body and is a member of the carpet shark family. This shark has the ability to 'walk' by using its fins just like feet. This adaptation helps this shark navigate its way through rocky reefs looking for food.

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Least concern

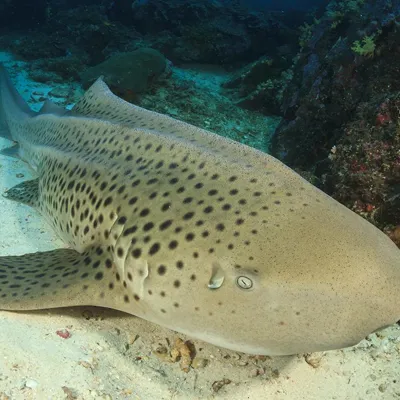

Leopard Shark

The Leopard shark also commonly known around the world as the Zebra shark is a slow-moving species that feeds on the sandy bottom on the sea primarily on molluscs and gastropod. This species grows to around 2.4m but has been recorded around 3.5m long.

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Endangered

Tawny Nurse Shark

Tawny Nurse Sharks or the Rusty Cat Shark can be found in the warmer waters of the north Australian coast. This species belongs to a family of sharks called the carpet sharks. Tawny sharks tend to spend the day resting among coral reefs or rocky substrate and is most active at night. This species of shark can grow to about 3.2 m in length. You can find our Tawny Nurse sharks in our Day and Night on the reef exhibit!

IUCN Red List Conservation status: Vulnerable

FIN-tastic Shark Facts

Species of Sharks

Did you know there are over 400 different species of sharks! Here at SEA LIFE Sydney we have 13

No dentist needed

Many species of sharks have several rows of teeth which they can lose and replace thousands of times in their lives.

Big and small!

Sharks come in all shapes and sizes. The biggest sharks today can grow up to 12 meters long and the smallest is around the size of your hand!

Under threat

Sharks are in danger of disappearing. Many sharks get caught in fishing gear or are hunted for their fins.

Shark Dive Xtreme

Dive with Grey Nurse Sharks in the heart of Sydney CBD!

- No cages - just you, your instructors, sharks, giant stingrays and more

- No previous diving experience required (age 14+)

- All day aquarium admission included

Meet Our Sharks

Meet Murdoch the Grey Nurse Shark

Murdoch is a very special shark, as he is one of only a few Grey Nurse Sharks born in human care. Grey Nurse Sharks are critically endangered along the East Coast of Australia, and Murdoch serves as an important ambassador for the species. Each year, he educates thousands of aquarium visitors about the vital role sharks play in the ecosystem and helps them understand why Grey Nurse Sharks are often referred to as the ‘Labradors of the Sea.’

SURPRISE! It’s a Baby Shark!

Historic Grey Nurse Shark Birth Captured on Video at SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium

In a jaw-dropping moment of marine history, SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium has announced the rare arrival of a baby grey nurse shark! The tiny yet mighty male pup, affectionately named Archie by the aquarists, marks a world-first for SEA LIFE Sydney, capturing hearts and making waves in marine conservation.

During a routine check-in at the aquarium’s Shark Valley, the aquarist team witnessed and filmed this extraordinarily rare event, as baby Archie made his debut - emerging from his mother, Mary-Lou and immediately swimming alongside one of the adult sharks. Grey nurse shark pups are independent from the moment they are born.

Born on November 15, 2024, Archie is now four months old, measures 74cm in length, and currently resides in the aquarium's specialised nursery pools - where he can focus on growth and development. The healthy pup is expected to grow approximately 30 centimetres each year and will eventually reach an impressive 3.2 metres in length

Latest Shark News